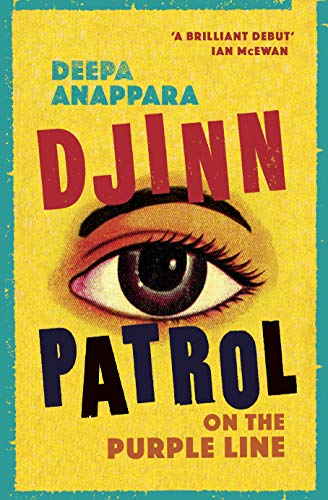

Set in a basti, an overcrowded area on the outskirts of a big Indian city, constantly under threat of being bulldozed and edged by a rubbish dump, Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line is a dynamic and engaging story that takes on the difficult subjects of religious division, social mobility, child abduction, politics and poverty with a surprising sense of hope and energy. Right from the start we are immersed in the characters’ minds, seeing the world through their eyes with impressive clarity.

Despite the horror of the subject matter – children are disappearing from the basti and as more and more disappear, it can’t just be a matter of children running away – Deepa Anappara speaks from the children’s perspective with such care and generosity that there is refreshingly little room for pity or condescension.

Nine-year-old Jai is the hero of the story. Obsessed with cop shows on TV, he thinks he knows how to solve the disappearances and gets his bestfriends Faiz and Pari to help him. Wanting them to be his side-kicks it soon becomes clear that Pari, who gets much better grades than him, has a knack for asking questions and Faiz, who is often busy working, is too keen to put the disappearances down to the djinns.

We become part of the neighbourhood, learn of the children’s hopes, ambitions and sadness about their future, hearing the stories of the ghosts who protect children, making it harder and harder to take the increasing loss of more girls and boys. We hear the adult stories of struggle and despair, the increase in tension in the neighbourhood in a way that the children don’t. We worry about heightened religious division and hatred, about the police coming with bulldozers, about the values of local politicians and gurus, whilst Jai continues to work on his suspect list, hoping his new job as a tea boy – kept secret from his family – and his knowledge of TV detectives will be enough to bring answers.

Anappara manages to keep this novel deceptively light and funny despite the bleak themes. We see this community’s struggle for fairness, justice and dignity continuing regardless of the system set up to sideline their interests in favour of the high-fi men and women they work for. Jai unwittingly becomes a spokesperson for social upheaval and the writing has such empathy, sensitivity and generosity, it is a joy to read. No wonder it hit the Women’s Prize Longlist this year.

I’ll be reviewing Against The Loveless World by Susan Abulhawa next.