Salmon Rushdie calls the novel ‘Extraordinary, ambitious, evocative, dazzling’ and I agree that The Old Drift is all of these things. The host of characters from English, Italian, Indian and African, like tributaries to the giant Zambezi, all flow into one family as the novel takes us from the colonial past of Victoria Falls and the creation of the Kariba Dam, into the future when new technologies merge with age-old biology to create a buzzing humming chorus to an exploration of the birth and establishment of Zambia.

The Old Drift is brimming with the politics of colonialism and its imperial capitalist hangover, but it is also alive with story and filled with characters and gods of multiple traditions. Myth and science fiction play together. One Italian, Sibilla is covered in hair so thick and fast growing she must cover herself and shave her face several times a day. English Agnes is blind and falls in love with a black man before she even knows the colour of his skin, but sometimes her skin seems to flicker as if covered with the many eyes of Argus. And there is the chorus of course, the buzzing and seeming malarial mosquitoes that swarm and carry disease, that later mate with nano-drones and lift technology out of human control.

As you see, the novel covers huge areas of human life and the interconnectedness of all the stories is not only delightful, it forces a constant revision of what has gone before, an endless reinterpretation of history. The Old Drift is very clever indeed. We read about missionaries and colonial racists. We see the dynamic between the master and the servant, the educated and the self-educated, the rich and the poor and the complex tensions and prejudices over skin colour. We look at the HIV crisis and the possible uncovering of a cure and how Zambia and other poorer nations continue to be exploited as test subjects for chemical and technological advancements in a global economy. Climate change takes on a new moniker, The Change; its effects no longer dismissable even to the most stubborn.

Alongside the grand subjects are the human characters each of whom has their own trajectory and personality. We follow their lives closely and feel the rise and fall of their ambitions and prospects. There is such a swarm of stories, told over such a length of time that it begins to feel as if humans too are part of that haze of insect voices, a plague upon the earth, living out a time that will one day pale into insignificance in the wider turns of the universe.

I suspect a further reading would unveil deeper levels of meaning and there are undoubtedly stories that I have not fully understood, but whether you are reading the novel for the journey of its characters or the urgency of its message for change, The Old Drift is a formiddle and gripping read. A very worthy winner of this year’s Arthur C. Clarke Award.

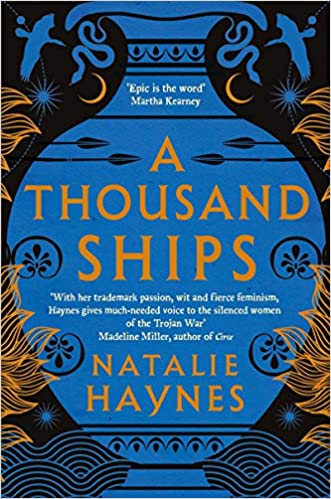

I’ll be reviewing A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes next.