Both novellas in the collection, Werther Nieland and The Fall of the Boslowits Family, have a strange air of directness to them. Set in Amsterdam in the Nazi occupation, the voice of the child in each instance has a self-absorbed air that distances the narrator, shows them to be too busy with the anxieties of youth to clearly see the wider implications of the situations unfolding around them. Continue reading Childhood: Two Novellas by Gerard Rose trans. by Sam Garrett

Both novellas in the collection, Werther Nieland and The Fall of the Boslowits Family, have a strange air of directness to them. Set in Amsterdam in the Nazi occupation, the voice of the child in each instance has a self-absorbed air that distances the narrator, shows them to be too busy with the anxieties of youth to clearly see the wider implications of the situations unfolding around them. Continue reading Childhood: Two Novellas by Gerard Rose trans. by Sam Garrett

Month: December 2018

Nothing Holds Back The Night by Delphine de Vigan

This autobiographical novel has won several prizes and it is obvious why. A biography of the narrator’s mother, Lucile, the book is self-reflexive, critical of its own approach and the narrator’s ability to summarise the experiences of a woman she only really knows from one angle, that of daughter. Continue reading Nothing Holds Back The Night by Delphine de Vigan

This autobiographical novel has won several prizes and it is obvious why. A biography of the narrator’s mother, Lucile, the book is self-reflexive, critical of its own approach and the narrator’s ability to summarise the experiences of a woman she only really knows from one angle, that of daughter. Continue reading Nothing Holds Back The Night by Delphine de Vigan

The Farm by Joanne Ramos

When I began describing the plot of this novel to a friend, they said, ‘Oh, that sounds like that series I saw on Netflix, you know, where not many women could conceive anymore and they were getting the fertile ones to be surrogates.’ Before he helpfully pointed it out, I hadn’t thought about the links to Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale because The Farm doesn’t need any change in regime, or depletion in fertility, for its surrogacy plans to flourish. It wouldn’t even surprise me if such a place already existed.

When I began describing the plot of this novel to a friend, they said, ‘Oh, that sounds like that series I saw on Netflix, you know, where not many women could conceive anymore and they were getting the fertile ones to be surrogates.’ Before he helpfully pointed it out, I hadn’t thought about the links to Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale because The Farm doesn’t need any change in regime, or depletion in fertility, for its surrogacy plans to flourish. It wouldn’t even surprise me if such a place already existed.

By mentioning The Handmaid’s Tale there is a sense in which The Farm can be downplayed as a bandwagon book, but what is pleasing about The Farm is that, regardless of its compelling narrative, it plays out the various sides of the argument for the existence of an expensive, surrogacy service that takes young, poor, mostly ill-educated and often immigrant women, and uses their bodies – monitoring them intensely, providing all their nutritional and physical needs – to give the babies they carry the best chance of healthy delivery. Continue reading The Farm by Joanne Ramos

Small Country by Gaël Faye trans. by Sarah Ardizzone

Gabriel, or Gaby, is a half-French, half-Rwandan boy living in Burundi. His mother fled Rwanda in the last Rwandan war. She is Tutsi. The tribal, ethnical, and national divisions seem distant from Gaby at the beginning of the novel, but as Small Country develops, the young boy is forced to take sides. From the safety of his street he is forced into the bloodshed.

Gabriel, or Gaby, is a half-French, half-Rwandan boy living in Burundi. His mother fled Rwanda in the last Rwandan war. She is Tutsi. The tribal, ethnical, and national divisions seem distant from Gaby at the beginning of the novel, but as Small Country develops, the young boy is forced to take sides. From the safety of his street he is forced into the bloodshed.

I thought I would love this story. I felt moved by its outlines, ensnared by its promises of what might unfold, of the awkward dissonance of belonging and difference. In many ways I did get what I was expecting. I was taken into Burundi. I could dip my toes into Lake Tanganyika. I was made to understand what it might feel like to hide on cold tile corridors, bolstered by multiple concrete walls far from windows. And yet…

In Chapter 23, Gaby writes about his friend who wins an argument by expressing his grief. He says, ‘Suffering is a wildcard in the game of debate, it wipes the floor with all other arguments’. In a sense any lack of appreciation I feel towards the book sits on this difficult boundary especially as there was so much to admire in Small Country. I particularly enjoyed the ending. It leaves a challenging, bitter taste in the mouth, questioning foreign interaction and interference in Africa, making Gaby’s mother a symbol of what is left after the fighting is done. And yet I still feel somehow at the same distance from events as Gaby appears to be, despite what he was forced to do.

I’m sure many will enjoy Small Country – it has beauty, poise and shows just how oddly politics can transmute into children’s lives – but I didn’t fall in love with it.

Next week I’m reading The Farm by Joanne Ramos.

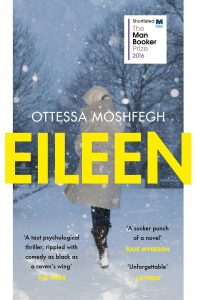

Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh

Eileen is a delightful read. One of those tight novels that explores the self-pity of late adolescence and early adulthood. The narrator is an older woman looking back on the girl of her youth. ‘There’s no better way to say it: I was not myself back then. I was someone else. I was Eileen.’ (p2)

Eileen is a delightful read. One of those tight novels that explores the self-pity of late adolescence and early adulthood. The narrator is an older woman looking back on the girl of her youth. ‘There’s no better way to say it: I was not myself back then. I was someone else. I was Eileen.’ (p2)

Eileen is in her early 20s. She gave up college to come home and look after her dying mother. Once her mother was gone she stayed home to keep her drunk ex-cop father in check. It’s a responsibility she bears with exhaustion and invention. To stop him behaving recklessly she locks his shoes in the boot of her car. It keeps him inside for most of the winter at least. Continue reading Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh