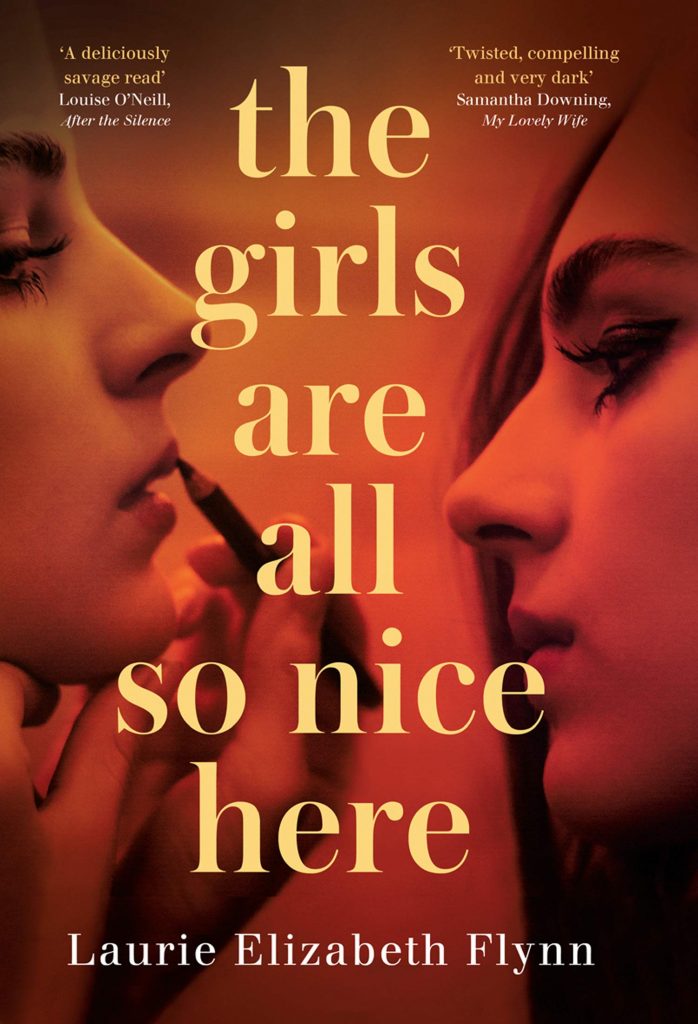

The Girls Are All So Nice Here is a real thriller exploring the lengths some women will go to keep their best friend.

I’m not sure I’m the target audience for this novel. Though I did pretty much read the book in one sitting, unable to leave the page before I found out quite what dreadful event happened all those years ago at University, I found the exploration of obsessive female friendship somehow outdated. These young women were so firmly situated in their roles within the patriarchy that though they may have been invented to challenge it, to show how stereotyping women could have horrifying consequences when those very women used that stereotype for their own means, they instead felt unreconstructed, rigid caricatures. But again, perhaps I wasn’t quite the right reader.

The writing is certainly compelling and written with twists in just the right places to keep you guessing. It also begins with a reunion. That kind of hook is hard to ignore.

If you like a campus mystery with mean girls whose behaviour is more acerbic than most you can think of on our screens, then this darkly twisted tale will be right up your street.

I’ll be reviewing Body of Stars by Laura Maylene Walter next.