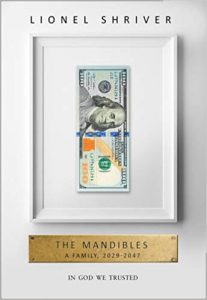

After reading We Need to Talk About Kevin and The Post-Birthday World, I wasn’t sure I’d be tempted to read another novel by Lionel Shriver. I’d found We Need to Talk About Kevin an issues based novel whose characters didn’t quite convince me and I seem to remember feeling mildly unmoved by The Post-Birthday World. Reading The Mandibles brings all the good sides of Lionel Shriver’s fiction – her snappy dialogue, her delight in conflict, her interest in topical issues – and shows them off to their best. My readings of her previous novels feel harsh and I begin to understand what it is that motivates Shriver and what makes her a fascinating writer to read. Being provocative isn’t just about getting people to read your book, it’s about getting people to think and The Mandibles really does get you thinking.

After reading We Need to Talk About Kevin and The Post-Birthday World, I wasn’t sure I’d be tempted to read another novel by Lionel Shriver. I’d found We Need to Talk About Kevin an issues based novel whose characters didn’t quite convince me and I seem to remember feeling mildly unmoved by The Post-Birthday World. Reading The Mandibles brings all the good sides of Lionel Shriver’s fiction – her snappy dialogue, her delight in conflict, her interest in topical issues – and shows them off to their best. My readings of her previous novels feel harsh and I begin to understand what it is that motivates Shriver and what makes her a fascinating writer to read. Being provocative isn’t just about getting people to read your book, it’s about getting people to think and The Mandibles really does get you thinking.

My scepticism of her previous work is one confession over with, the next is that I know very little about economics. Given that The Mandibles is all about the economy on a local and global scale, how it drives all aspects of governance and society, my reading of the novel will undoubtedly be different from someone with sound economic knowledge.

Ok, now I’ve confessed it all, you’ll know where my review is coming from.

The Mandibles are an American family whose head, Great Grand Man, has a fortune (from his forebears) to leave to his children and their children’s children. At the start of the novel his family are living with the knowledge that one day they may receive some of this fortune, though none of them seem to know how much money there really is. Some of children and grandchildren have done well for themselves, some struggle.

Then the dollar collapses.

In one fell swoop the fortune has gone and different echelons of the Mandible family are thrown together in ways they couldn’t have expected.

Race, class, governance within America as well as outside of it, are all explored. There is a sense of post-apocalypse. There are journeys across states that harp back to images of pilgrims in wagons cross-wired with images from Stephen King’s The Stand and it is a delightful mix. This playfulness over our near-future, the knowing, rye sense of irony one would feel escaping a city in the wake of large scale governmental collapse, after all those books and tv series and films, make The Mandibles a fun read despite the serious subject matter. Being a Grand Man, Great or otherwise, is relative.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this novel. Particularly I appreciated the humour and the hope.

At the centre of the family and the heart of the novel is Willing. 13 when the novel starts, he is one of the younger members of the family but also one of the most watchful and reflective. Though novels are no longer written – too much rubbish churned out for free that no one bothers to write or read anymore – being an observer, someone who stands back, remembers and considers the world around them, is something to be valued. It is Willing and his great aunt, Enula or Nollie, a once novelist who emigrated to France, who form the emotional heart of the book. And rather than find this annoying, once again Shriver manages to hit just the right note, and this line of the plot feels amusing, another interesting perspective on how to survive in a fast-changing world.

There are a lot of different areas one could talk about, but I feel as I’m attempting to write a review that might encourage you to read the book, I should stop before I start revealing parts of the plot. I’m happy just to recommend a page-turning riot of a novel that explores the fragility of fiscal supremacy, of empire in all its guises, of currency full stop, but then laughs at the difficulty of finding a suitable replacement.

I’d love to hear what any of you think of the novel. The Mandibles is full of, and made to start, discussions.

Next week I’m reading Compass by Mathias Enard.