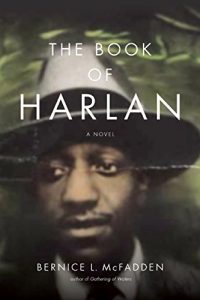

The Book of Harlan is exactly that and more. It tells the story of a man named Harlan from his very beginnings, including the history of his parents, until 1973. As we follow his story through the musical heights of Harlem in the 1920s and 30s, into the Second World War and beyond, we are exposed to a host of characters who fill Harlan’s life.

Harlan is not a lone character, but a man connected to family and friends, to his work, his country and the wider world. You cannot read about Harlan without reading about the history of the first half of the 20th Century. But instead of reading a history so many of us have read before, this is history from the perspective of a black American.

Much of the press surrounding the book, centres on Harlan’s experience of the Holocaust. This is his mother reflecting on a doctor’s visit to Harlan:

What if what the doctor said was true? She’d read about what the Jews had gone through in those camps; she’d seen the devastation for herself in a black-and-white newsreel that screened before the main feature of a movie she could no longer recall.

She didn’t remember seeing any black people in the footage, so Dr. Carter must be mistaken. It was just Jews who were interned and murdered in those camps. Wasn’t it? She hadn’t heard any different. Every time the news reported on the Holocaust, they talked about the Jews and no one else. There was certainly no mention of Negroes—she would have remembered that. Yes, Dr. Carter must have his facts wrong. (p.243)

It is important that the novel exposes the gaps in our understanding of World War II, but the novel doesn’t really dwell on the experiences of the camp as Harlan lives through them, though the horrors are there. Instead, as well as proving impossible to recover from, the camp becomes a symbol for racism and prejudice experienced in America and South Africa. The people who won’t let their son play the blues (Harlan’s friend Lizard is a Jew who fled Germany and pretended to be black to play negro music only to end up incarcerated in a German death camp), or who put extra locks on their door when black families move into the neighbourhood, or the policemen who treat black men with brutality, all feel like extensions of Hitler’s ideology, an ideology that continues to run rife through America and the rest of the west. It is impossible to read Harlan’s story and not take a long hard look at your own attitudes and those of your neighbours, your law enforcement and your government.

As Harlan walks off into the night sky at the end of the book, the policeman he’s just encountered has reminded him that “the world is round” (p.330). The Book of Harlan is a rich tapestry of a novel that reminds readers that what goes around comes around. What should come first and foremost, above all else, is the ability to listen and to treat others with respect.

At the very end, McFadden quotes Dorothy West, ‘There is no life that does not contribute to history’. The Book of Harlan is a provocative and gripping read that will no-doubt entice a wide and eager readership. Thank you Jacaranda Books for bringing it to the UK.

I’m now reading The Weight of Things by Marianne Fritz.