It’s the summer of 1976 in England. The hottest summer on record. Nif’s little sister, Petra drowned in the bath four months ago and the family take off to a small village on the Welsh border to escape the grief that seems to be sucking the life from their family.

It’s the summer of 1976 in England. The hottest summer on record. Nif’s little sister, Petra drowned in the bath four months ago and the family take off to a small village on the Welsh border to escape the grief that seems to be sucking the life from their family.

Nif is sixteen and no stranger to looking after Petra’s twin, her little brother Lorry. His speech is slow and he’s just come out of nappies even though he’s four years old. When he falls over on the gravel path outside the cottage in Wales, Nif rubs gravel into his other knee – it’s the Creed, the Creed that makes her do it. Things need to be balanced out.

When they arrive, they soon realise they aren’t the only outsiders in the village. Their neighbours, Janet and her son, Mally, are strangers too. Janet has a lush garden, a home filled with dried herbs, likes to drink and can divine water. She has a mesmeric, attractive if somewhat garish personality that draws in both of Nif’s parents but has the village up in arms. Mally soon becomes her friend by leaving a bird’s skull on the railings, just for her. Bird skulls, bird artefacts in general – wings, eggs, dead chicks – are all important to the Creed. There’s something that Nif wants to remember about the night of her sister’s death and she’s certain the Creed will help her.

But what is going on in the village? On Sundays Nif watches the churchgoers flick water towards Janet’s property. Their lanky silent preacher is blind, his eyes covered in a milky white film. Mally photographs them all with the polaroid camera he carries everywhere.

Added to this heady atmosphere of teenage sexuality, religious fever, witchcraft and grief, is the stifling weight of the heatwave. Everything suffers under the force of the sun that bakes the ground and douses everyone in sweat, dulling the speed of their thoughts, casting its spell upon their bodies and minds. This dream-like haze is what makes the novel so exciting to read. It carries a real sense of threat and unnerving possibility.

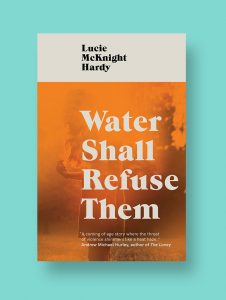

I won’t say more about the plot as that would spoil it, however, while the revelations feel pleasingly seeded, not every one is expected and the novel ends with a sense of you longing for it to go on. Delightfully infused with the feeling of unease, Water Shall Refuse Them cleverly exploits our discomfort around old folk law, pagan religion and our need to impose meaning on the most confusing of feelings and events. Published by Dead Ink, it’s a prompt to encourage you to get your hands on more of their books. Have a look here.

I’ve been slow to review recently, despite reading at the same rate. Sorry for that. I’ll be reviewing Rosewater by Tade Thompson next.