Sameer is an extremely hard-working commercial lawyer from Leicester, living and working in London. He has money, a nice flat in Clerkenwell, and enough good friends to fill the hours outside the office.

Everything changes when one of his oldest friends, Rahool, decides to move back to Leicester and work in the family firm. His other close friend, Jeremiah, also has a new job and though it looks as if Sameer’s career is going well – he has after all been offered a job setting up a new office in Singapore, which would be a huge promotion – he can’t quite bring himself to tell his family, partly because they’ll be disappointed he too isn’t returning home to the family business, but partly because the departure involves an acknowledgement of the racism he faces from some of his colleagues that up to this point he has decided to overlook.

Things are pushed to an even greater level of tension when Rahool is beaten into a coma in a racially motivated attack, only weeks after returning to Leicester. Sameer and Rahool are second generation immigrants whose parents were forced to leave Uganda when Idi Amin expelled all the Asians. They have no memory of Uganda, but they live with the pressure of their parents entrepreneurial success, success hard-earned from their status as refugees with little money or connection to their names.

Interspersed with this contemporary narrative are a series of letters from Sameer’s grandfather, Hasan, written to his first wife after she passed away. These letters form an account of his life in Uganda as the regime changes and what happened after he and his family were forced to leave and eventually take refuge in England.

I don’t want to say more about the plot, because that would spoil the book, but both narratives explore religion, racism and love. They look at what it means to have and share beliefs across the boundaries of race, nationality and religion in friendship and in desire.

It took me some time to get into the letters, initially they felt a little contrived, constructed to carry the history of Sameer’s family. I was more taken with Sameer’s contemporary account, but over time I was drawn into the events of Hasan’s life and there are passages of remembered dialogue and a few unexpected twists that keep the account from feeling too expositional.

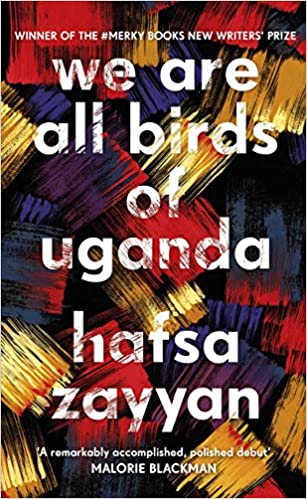

We Are All Birds of Uganda explores the wider fall out of empire in intriguing ways, asking us to look again at national identity and race. I’ve no doubt it will be a novel much talked about in 2021. I think more than anything I admire the ending. I’m not going to spoil it, but let’s just say I like books that leave you wondering what will happen next. Out now, it’s a very impressive debut, sure to appear on some prize lists this year.

I’ll be reviewing The Girls Are All So Nice Here by Laurie Elizabeth Flynn next.