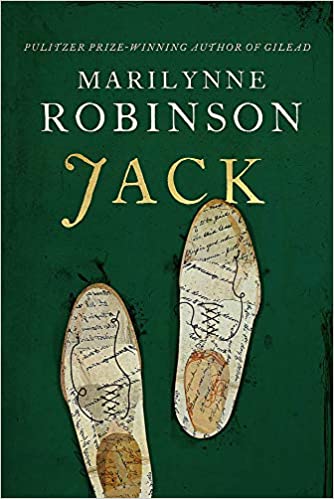

I’m a huge fan of Marilynne Robinson. Lila remains one of my favourite books. I opened Jack hoping for that same careful attention to the twists and turns of consciousness. I wasn’t disappointed.

Jack hails from Gilead, the Iowa town that provides the setting for three previous novels of which Lila is one. He is the prodigal son of Gilead’s preacher who has done his best to stay away, thinking his best road is one in which he attempts to be harmless and going home might cause more harm than good.

Jack falls in love with Della, an African-American girl, at a time when interracial marriage was against the law.

The novel is structured so carefully (though not sequentially, more like the workings of memory than a sequence of events), letting us fall in love with Jack in the same way that Della does, revealing his better nature before taking us back to the parts of his past he is least proud of and their interactions are so delightfully considered, both of them children of preachers, both of them educated – Della is a teacher, Jack let his brother take his exams but reads and loves poetry nonetheless – that it is hard not to hope for this pair of lovers despite Jack’s rather disreputable past. There is something about his attempts to fit in, to leave society unruffled by his presence, that makes us feel for him the way Della does. Though, in truth, he’s probably a cad and Della would have an easier life without him.

There is such a delicate moral unpicking in Robinson’s work. Every dilemma is held up against religion, always waiting for one side or the other to trip up over its own logic. This kind of unpicking feels interestingly uncontemporary. This is something that takes time. These are people who need lengthy conversations and who write letters. I suspect this is part of the reason Robinson enjoys writing about these historical eras. We are so geared towards speed in our current lives that writing like this demands as much attention as its characters give to their thoughts. This won’t be for everyone. You need to sit and listen. The hymns, the biblical reference, the quiet challenge of the authority of the church and of society is loudest when you give the novel space. This is not a book you can skim through because though the plot is important, it’s how the characters get there, what they think along the way, that’s the truly fascinating part.

The novel begins in a cemetery. They both get locked in for the night. Della is locked in by accident. Jack had already planned to stay the night. They have already met, but this night together in chaste companionship creates a bond, an atmosphere that is magical, spiritual in its mists and lake-reflected starlight, in the dark shadows cast by stone angels.

There is no need to have read any of the previous novels to enjoy this one. If you like reflecting upon what it means to play a role in the organised structures of our societies and religions, and what it means to decide to act against or outside of them, Jack is just the book for you.

I’m reading The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell next.