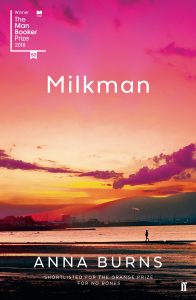

As the winner of The Man Booker Prize 2018, Milkman has had a lot of reviews and many words shared over it. Part of my reason for wanting to read the novel was because it has been described by some as ‘difficult’. I’m never really sure what people mean when they say a novel is difficult and I was intrigued to decide for myself quite what it was they meant in this instance.

As the winner of The Man Booker Prize 2018, Milkman has had a lot of reviews and many words shared over it. Part of my reason for wanting to read the novel was because it has been described by some as ‘difficult’. I’m never really sure what people mean when they say a novel is difficult and I was intrigued to decide for myself quite what it was they meant in this instance.

Milkman is the story of middle sister who lives in an area of Northern Ireland controlled by the local renouncers. She likes to read eighteenth-century literature while she walks. She likes to run and she likes to take French classes somewhere where people from both sides of the Troubles can meet and where her teacher ‘from over the water’ discusses the beauty of sunsets that challenge the accepted monotone colour description of the sky. She also has a maybe-boyfriend in another area that not everyone – certainly not her mother – knows about. She doesn’t act as she should. She lives as if the Troubles exist outside of her, as if they don’t affect and control her.

The title is also the name of a dangerous paramilitary who decides to take a fancy to middle-sister. Once seen with her, the rumour mill builds to a fevered pitch and the careful grooves she’d worn into her life to keep her own special kind of hidden sanity, prove no match for the world’s intervention.

The novel explores the impossibility of standing outside of politics, and shows this particular set of troubles to be one which controls the tiniest aspects of people’s lives to a debilitating extent.

One of the reasons I think it is described as difficult is because of the style of the prose. The sentences often spin away into additional explanatory, or semi-explanatory, clauses that then need further clarification. Life in middle sister’s Northern Ireland is confusing and so too are the sentences. Not every sentence is long with multiple clauses, but enough are to be considered, I suppose, difficult.

Characters are also only ever referred to by the names given to them by the community, either who they connect to in the family (e.g. middle sister) or how the community refers to them (e.g. tablet’s girl). This distances the reader from the people at the heart of the characters and whilst this lends a mythic quality to the story, it also forces the reader to pay a dual attention to the characters as people and roles, as individuals inseparable from their allotted space within the community.

Both the sentences and the naming require attention from the reader and I would suggest that difficult also implies requires attention. For really that is all the reader needs to do. You simply need to pay attention, something Milkman is all about. You can’t afford to not pay attention in life. In this way, the novel’s expression matches the story that it tells.

I should be honest and say that whilst I deeply admire the way Milkman is written, I didn’t always enjoy reading it. There were times when I was fed up with middle sister’s story and with the way she was telling it, but again this mirrors what she feels herself.

The story is a beautiful comedy in an Irish tradition in which the underlying mood is frighteningly black. The Daily Mail said ‘If Beckett had written a prose poem about the Troubles, it would read a lot like this’ and in many ways I agree, but what Anna Burns brings is a deeper sense of the effects the Troubles have on local social communities, individuals, in other words the domestic sphere. It’s hard hitting, upsetting, funny, annoying and brilliant. Another way in which it is difficult is because it’s hard to read something in which individuals have their freedoms so circumscribed by their community. It’s difficult because Milkman says wake up and make the most of your freedoms while you have them.

Next I’ll be reviewing May We Borrow Your Country: An anthology of short stories and poems from The Whole Kahani collective, just published this January 2019.