Fire on the Mountain is a formidable novel. Like a mountain itself it is daunting and alluring. It stands loudly in the landscape, crying to be made sense of, the air thinner at its summit, more rarified, the winds harsh against it. The writing is searing and fierce, though even the most minutely explored character has a complexity that allows for empathy whether we like them or not. To summarise the novel, is to diminish it because it is about much more than the plot, but I’m going to give you a brief sense anyway (no spoilers you don’t get from the back cover, I promise).

Fire on the Mountain is a formidable novel. Like a mountain itself it is daunting and alluring. It stands loudly in the landscape, crying to be made sense of, the air thinner at its summit, more rarified, the winds harsh against it. The writing is searing and fierce, though even the most minutely explored character has a complexity that allows for empathy whether we like them or not. To summarise the novel, is to diminish it because it is about much more than the plot, but I’m going to give you a brief sense anyway (no spoilers you don’t get from the back cover, I promise).

NGO worker Nick arrives at this coastal African city, prepared to head into a war zone to offer refuge to the displaced, the dispossessed, and feels himself drawn to the landscape as if he had been there once before. Out of character, he walks from the ship and finds himself at the house belonging to his friend’s uncle, the famous writer Pieter Lisson and his wife, Sara. He doesn’t know what he’s doing there. The sense of dispossession hangs over his decision to abandon ship and slowly, as the days turn into weeks Pieter and Sara include him in their life, welcome him into their family and he finds himself spending Christmas with them at their northern beach house with their younger son, Riaan.

Nick is rudderless without the ship and his career, following Pieter and Sara’s patterns until Riaan presents something different, some new beacon towards which he directs himself. He goes to visit Riaan in the north, where the desert, hyena and leopard rule. He learns about Riaan’s charity work. He camps out under the stars and finds himself intensely drawn to Riaan regardless of their previous sexual history.

So much more than this happens. There is a hovering sense of the magical weave of dreaming that stands just beyond our usual cognisance, but which some people seem able to tap into, writers among them. There is a painful questioning of what it means to be a writer, of how that can form any kind of action in the world and there is also a cold eye cast over the white man’s obsession with Africa and the legacy of that obsession. Privilege, an international consciousness, are all explored for good and bad.

By the end there is a sense in which the novel tries to analyse itself. This high intellectual ground is shared with many of the characters who move in a milieu of wealthy do-gooders, and this may sadly turn some people away from a novel that asks us to rethink our place in the world. We need to think about the ways in which land and people call to us. We need to question the interconnectedness of past and present, of the international landscape in which we allow famine, industry and war to continue to ravage. All this burns on that mountain with the same intensity as the emotions of the characters who think, act and love with similar ferocity. The complexity of this world, and its complicity in so much of human history and human nature, makes the world of Fire on the Mountain a fascinating one, rich with symbolism, but not afraid to leave rough edges where the reality of life won’t be neatened by narrative, leaving parts that echo raw in a reader’s chest.

Fire on the Mountain is full of the restless longing to find where we are from, who we are, and how to be; to find our place. Fatherhood, nationhood, sexuality; Fire on the Mountain suggests these are all fluid ideas.

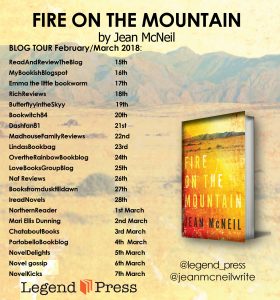

If you would like to get your hands on a copy of this fascinating novel, I have one copy to giveaway. You need only be the first person to comment on this blog and the novel is yours. This blog post is part of a blog tour for Fire and the Mountain. You can follow the rest of the tour over the next few weeks, details are included in the picture on the left.

If you would like to get your hands on a copy of this fascinating novel, I have one copy to giveaway. You need only be the first person to comment on this blog and the novel is yours. This blog post is part of a blog tour for Fire and the Mountain. You can follow the rest of the tour over the next few weeks, details are included in the picture on the left.

Next week I’m reading Sweet Days of Discipline by Fleur Jaeggy, translated by Tim Parks.